The Case of the Empty Specimen Jars

It was a dark and stormy night…

Casey was working late at the lab processing pathology biopsy specimens when she noticed that a specimen jar properly labelled with the patient’s name “Jane Doe” (and a second identifier) was empty except for a slight reddish tinge. Casey had opened the jar under the newly installed surveillance cameras, so she had evidence that in fact the jar was empty. She also called to her fellow worker, who verified the empty jar in accordance with the lab’s procedures. Casey set the empty jar aside for further investigation the next day.

The next specimen jar that Casey picked up was labeled “M.J. Smith:” (also with an appropriate second identifier). Again, the jar was empty except for the formalin and a tiny piece of lint! What was going on? The third specimen jar labeled “John Doe” was also empty except for the formalin.

Three specimens. Three empty jars.

Three specimens. Three empty jars.

The next day, the laboratory director Dr. Watson asked for the assistance of his good friend and colleague, Sherlock Holmes. Holmes breezed into the lab, sniffed the air and said, “the ventilation could be improved and the floor could use a waxing.” He closely examined the specimen jars. He quickly determined that the three specimens had originated from different physicians’ offices and had arrived by different couriers. The specimen manifests appeared to be in good order.

He took the first jar labeled “Jane Doe,” gave it to Dr. Watson and said, “My good Doctor, make a monolayer prep.” Then from a pocket in his deerslayer coat he pulled out an instrument labeled “Holmes Lintometer, patent pending.” He took the piece of lint out of the second jar labeled “M.J. Smith” and placed into the Lintometer. Next, he told Dr. Watson that he wanted to see all the reports and specimens that had arrived from the third physician’s office; and, he wanted any of the paraffin blocks from any prior biopsy on “John Doe”. Then Holmes said, “Watson, I want you to assemble everyone from those three offices in our parlour tomorrow morning.

“But Holmes, I can’t possibly get all of those people to attend, and besides we don’t have a parlour,” said Watson. Holmes was insistent. So by begging, pleading and bartering with offers of donuts, Novabucks’ mochas, flowers and massage coupons, Dr. Watson got everyone from the physicians’ offices to attend.

Holmes said, “What we have is a classic “locked room or locked box” mystery or in this case “locked jar” mystery. How did these specimens go missing? Holmes asked the first office what kind of specimen did you submit? The office staff said it was kind of glistening and mucoid. Holmes pulled a microscope out of a pocket of his deerslayer coat. “Watson, will you tell what you see on the monolayer prepared from the first specimen labeled Jane Doe”?

“I see red cells, white cells, mucous debris and a few mucous producing cells”

“Ah ha” exclaimed Holmes! “The specimen was there the whole time. It simply dissolved.”

Then Holmes asked the second office. Do you use a No. 2 Green Kimberly-Johnson surgical drape and a pair of forceps that comes in a disposable sterile pack?” The office manager answered, “Yes, but how did you know”?

“I discovered a piece of lint in M.J. Smith’s jar that my Lintometer identified. Thus, Indicating that the specimen had touched the drape. Furthermore, the forceps you used are notoriously hard to hold specimens. I believe, if you go back to your surgical waste from yesterday, you will find the specimen on the drape where it fell.”

“I discovered a piece of lint in M.J. Smith’s jar that my Lintometer identified. Thus, Indicating that the specimen had touched the drape. Furthermore, the forceps you used are notoriously hard to hold specimens. I believe, if you go back to your surgical waste from yesterday, you will find the specimen on the drape where it fell.”

To the third office, Holmes asked “ Do you pre-label specimen jars with the patient name before the patient enters the room?” The office nurse answered, “ Yes, we always make up our labels for possible biopsies each morning.” Holmes said, “I have reviewed all the specimens from your office yesterday. John Doe’s jar was empty, but Mr. Tiny Tim’s jar contained two specimens. I have with me the block from Tiny Tim’s biopsy and a previous biopsy from John Doe.” Then Holmes pulled out of a pocket in his deerslayer coat an instrument labeled “Holmes Instant Whole Genome Sequencer, patent pending” and proceeded to test the genetic code in the prior specimen and the two pieces of tissue in Tiny Tim’s specimen.

“Eureka, I mean, Elementary,” shrieked Holmes! The genome sequencer proves that John Doe’s biopsy was in fact placed in Tiny Tim’s jar.” “Well, my work is done,” he said as he grabbed a donut and a mocha. “And don’t forget to wax the floor.

Holmes had identified three of the most common reasons for a specimen jar to be empty. The first specimen was fragile, mucoid and dissolved. The second specimen fell on the sterile drape before making it into the jar. The third specimen was placed in another patient’s jar because of pre-labeling.

One of the great mysteries of laboratory medicine is: Where did my specimen go?

This conundrum is more common that you might think. Despite some solutions hopefully implemented in my years of practice, no one universal fix has emerged.

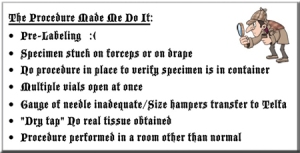

Possible procedural causes include the “ever fraught with terror” practice of pre-labeling containers. This attempt at being efficient often backfires with the usual unfortunate results. The well-intentioned provider may place the specimen in a separate unlabeled container during the procedure, which is inadvertently discarded. Then, the empty pre-labeled container is sealed and neatly tucked away in a specimen bag for shipment to the lab. Good procedure, poor results.

Other attempts fall short when tiny specimens get stuck on forceps and never make it into the jar or minute specimens drop off the forceps onto a sterile drape, and end up in the trash. Sometimes, the gauge of the needle size is too big. The transfer of the specimen to Telfa is somehow hampered and the specimen gets left in the needle. It, too, is later discarded, and the gauze ships sans tissue to the lab.

Because, we are only human, no foolproof method exists to verify the specimen is in the container prior to sealing. Errors invariably result. This causes additional anxiety for the patient, who never knows whether that first erroneous sample was relevant to their final diagnosis or not.

InCyte Pathology’s internal processes include visual inspection at the time of accessioning. If there is a question about the existence of a sample, a Pathologists’ Assistant verifies that the container is empty. This entire process is further documented by video cameras specifically installed for quality assurance.

InCyte Pathology’s internal processes include visual inspection at the time of accessioning. If there is a question about the existence of a sample, a Pathologists’ Assistant verifies that the container is empty. This entire process is further documented by video cameras specifically installed for quality assurance.

Sometimes, the specimen is too tiny or unstable and becomes so degraded in transit that it is invisible to the naked eye. When this is a possibility, the physician’s office is immediately contacted and offered the option of either spinning the specimen to see if there is enough cellular material to create a cell block or create a monolayer.

Ultimately, catching any specimen mix ups is most important at the time of excision or resection. Remember to confirm the presence of the specimen in the collection jar prior to sealing and shipping. Try the STOP – LOOK – SPOT approach to help remind staff who handle specimen containers to catch any problems before they become a much larger problem (the errant specimen is discarded).

- STOP what you are doing. There is no such thing as “multi-tasking”

- LOOK in the bottom of the container. Sometimes swirling the fixative can help identify the presence of tiny cellular material.

- SPOT the specimen and confirm the identify of the patient prior to transport.

No matter how many years you have been practicing your craft, routines are interrupted and the opportunity for error is heightened. Implement your own office safety procedures to avert the “mystery of the empty specimen container” and avoid unnecessary inconvenience and anxiety for your patients.

Now where did I put my keys?

Comments are closed.